As long as the reforms are kept on track, the RCEP will be the new driver for the economy to speed up the recovery process and later thrive in the post-pandemic period by further integrating into regional value chains.

Vo Tri Thanh*

On the very first day of the new year, the world’s largest free trade agreement – Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – officially came into effect. It is the second “mega-regional” trade pact in Asia and the Pacific, following the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) that has become effective in December 2018.

The RCEP covers a market of 2.3 billion people and US$26.2 trillion in global output. This accounts for about 30 per cent of the population worldwide and over a quarter of the world exports, which make the RCEP the largest FTA in the world.

The highly expected event of the year comes 60 days from the time when at least six ASEAN countries and three partner countries completed the procedures for approval/ratification of the agreement and deposited their instruments of approval/ratification with the ASEAN Secretary-General.

Australia and New Zealand were the latest member states to ratify the agreement.

After more than eight years of negotiations, 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and five dialogue partners including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand signed the RCEP on November 15, 2020 in the 37th ASEAN Summit chaired by Viet Nam.

Though some cast doubts on the ambition of the agreement as there are many divergences between some signatories who are the world’s developed economies and some others being much poorer and least developed, the ASEAN-driven agreement still came to conclusion after 30 rounds of negotiations and four summits.

RCEP and CPTPP

Before 2016, there were concerns over competition between CPTPP (called TPP before the US withdrew from the deal) and RCEP as the two trade pacts have quite similar objectives of trade liberalisation and economic integration. Some even feared that US-led TPP and RCEP in which China is a large member economy might come into conflict due to the long-standing feud between the two nations. They raised concerns that any competition between these two agreements might lead to division among ASEAN members, which might ultimately undermine ASEAN’s centrality in the region.

The memberships of the agreements overlap with seven of 11 CPTPP members signing the RCEP. They are Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Viet Nam.

However, since 2016 such concerns have eased off. There has instead had major arguments that RCEP and CPTPP actually supplement each other. RCEP includes 20 chapters covering most aspects of contemporary trade relations, many of which follow the chapters of the CPTPP.

Some studies by researchers also show becoming a joint member of RCEP and CPTPP will result in greater benefits than joining only one trade agreement or not joining any. Moreover, TPP/CPTPP and RCEP both are seen as realistic steps in forming the Asia-Pacific Free Trade Area (FTAAP) in the long term.

RCEP’s impact on Vietnamese economy

Despite being assessed as not high-quality and wide-ranging agreement as CPTPP (for example, it does not include provisions on labour and environmental standards or state-owned enterprises), RCEP is still expected to bring its members the benefits which will be more than twice those projected for the CPTPP agreement, according to an ADB Economics Working Paper released in October 2021.

RCEP promises to boost regional connectivity by rebuilding supply chains that have been severely disrupted during the pandemic, and promoting regional cooperation in trade and investment amidst the rising of protectionism and nationalism.

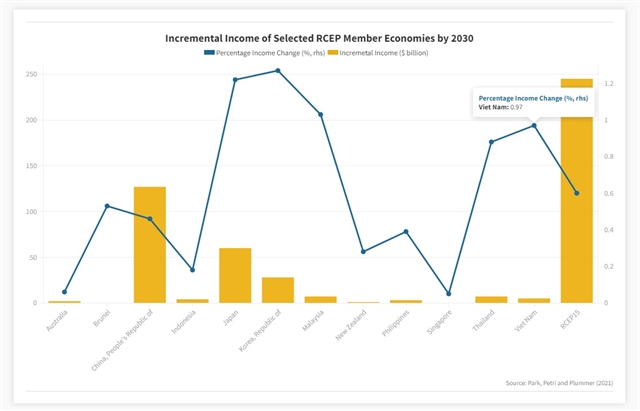

ADB economists estimate that if the RCEP is well implemented as scheduled, the agreement will increase members’ incomes by 0.6 per cent, adding US$245 billion annually to regional income and 2.8 million jobs to regional employment by 2030. This is of critical importance given the pandemic has dampened economic growth and caused job losses in many countries.

For Viet Nam, major export categories that are expected to benefit include IT, footwear, agriculture, automobiles, and telecommunications. The FTA would help Viet Nam access large consumer markets double the size of those included in the CPTPP.

Beside, with RCEP serving as a comprehensive legally-binding framework on trade, investment, intellectual property, e-commerce, and dispute settlement, we will have a long-term, stable, and predictable export market thanks to well-implemented, consolidated rules and streamlined regulatory procedures.

The simplification of procedures such as customs and rules of origin will help reduce bureaucracy, allowing more domestic small and medium-sized enterprises to participate in the value chain.

Foreign companies investing in Viet Nam can also benefit from lower costs brought by the common rules of origin.

During the implementation of previous free trade agreements (FTAs), many Vietnamese export products used raw materials imported from countries outside the FTAs, so they did not meet the origin requirements to enjoy tariff preferences. Now, China and South Korea, the two main raw material suppliers to Viet Nam, are RCEP members, so Vietnamese exports will have more chance to enjoy the preferential tariffs.

However, for Viet Nam, it should be noted that it will take years to see the benefits of the RCEP and it might not be as significant as the CPTPP and EVFTA.

In 2020, trade turnover between Viet Nam and RCEP countries already accounted for 55 per cent of the total revenue of the country, of which exports amounted to 41 per cent, and imports to 71 per cent. Thus joining RCEP does not naturally mean accessing more markets. Noting that many of the so-called ASEAN + 1 FTAs (between ASEAN and China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand) were already utilised for several years.

On the other hand, for most RCEP economies, Viet Nam is running trade deficits due to less developed supporting industries and shortage of capital goods. So due to easier movement of goods across the RCEP members, Vietnamese firms might face more competition both domestically and for export markets. Eventually, the trade deficit issue would probably be further worsened.

Failing to adapt to new competition would turn opportunities into challenges.

Policy implications for Viet Nam

Studies conducted by economic research institutes show some areas where RCEP can help Asian economies in general and Viet Nam, in particular, to rebound from the pandemic, namely trade liberalisation, regional investment, digitalisation and institutional reform.

Can Viet Nam take advantage of RCEP or not rely on the political will needed to undertake its deep regulatory improvements.

First, Viet Nam needs to continue implementing reforms to the macro-economic foundation in general, including competition policy, business environment, and production factor markets. These reforms must aim at maintaining macro-economic stability and strengthening the resilience of the economy.

Second, trade policy needs to be consistent with investment policy, thereby contributing to more effectively handling of trade deficit and import of intermediate goods; and at the same time be suitable with the participation of domestic enterprises into the RCEP regional value chain.

Trade policy should focus on four main contents, including: (i) Renovating mechanisms and policies for import and export management and administration: (ii) Enhancing the competitiveness of Vietnamese goods; (iii) Focus on sustainable development of the domestic market; (iv) Promotion of export combined with orientation of exporting activities; and (v) Facilitation of importing and exporting essential items in the context of COVID-19.

Third, Viet Nam needs to deal with bottlenecks in infrastructure and human resources to attract more FDI not only from RCEP economies but also countries outside RCEP.

Fourth, RCEP takes a pragmatic approach to the digital economy, a sector that rose in importance during the course of the pandemic. Thus, investment in ICT development to promote e-commerce is also a must.

Finally, it is also necessary to promote dissemination activities to help local businesses to gain a better understanding of Viet Nam’s commitments and possible impacts from the RCEP to maximise its benefits.

Effective prevention of the COVID-19 pandemic is still a short-term requirement. The important point here is that all the reforms must be carried out promptly and immediately, instead of waiting until the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As long as the reforms are kept on track, the RCEP will be the new driver for the economy to speed up the recovery process and later thrive in the post-pandemic period by further integrating into regional value chains and Asia-Pacific region in general. VNS

*Vo Tri Thanh is a former vice-president of the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM) and a member of the National Financial and Monetary Policy Advisory Council. The holder of a doctorate in economics from the Australian National University, Thanh mainly undertakes research and provides consultation on issues related to macroeconomic policies, trade liberalisation and international economic integration. Other areas of interest include institutional reforms and financial systems.

- Tags

- RCEP