The Ministry of Investment and Planning has issued a warning against borrowing from the Official Development Assistance (ODA) source fearing the country could fall into an “ODA and preferential loan’s trap”. Whether ODA will be the "trap" of the economy in the medium and long term depends on our ability to change ourselves, economist Vo Tri Thanh says.

In mid-August, the Ministry of Investment and Planning (MPI) issued a warning against borrowing from the Official Development Assistance (ODA) source in its report on ODA attraction, management and use over the next two years.

The ministry urged that if Viet Nam continued borrowing without careful consideration, the country could fall into an “ODA and preferential loan’s trap”.

This reminded us of a story in Malaysia where Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad recently announced that China-financed projects in his country worth billions of dollars would be put on ice.

The projects include a US$20 billion 688km-long East Coast Rail Link, which would have connected Malaysia’s east coast with southern Thailand and the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur, and two gas pipelines worth $2.3 billion.

The reason behind his decision was that his debt-ridden country cannot afford and cannot repay such a huge amount of money amid ballooning national debt, which was estimated by the Malaysian Ministry of Finance to reach approximately $250 million as of May this year. Of the total, federal government debt and liabilities accounted for about 80 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product.

It can be said there are similarities between Viet Nam and Malaysia as both are developing countries with limited budgets, therefore both of them have to depend on external capital sources to develop.

However, has the public debt situation in Viet Nam become so serious the country has to stop borrowing ODA loans or cancel several projects as Malaysia did?

To answer the question, we need to look back to the pros and cons of such a capital source as well as the real situation of the Vietnamese economy.

In the past, the ODA capital was preferred thanks to its low interest rate and long payback period which normally lasts 25-40 years, with a grace period of 5-10 years. Before 2010, the interest rate of ODA lending was just 0.7-0.8 per cent per year.

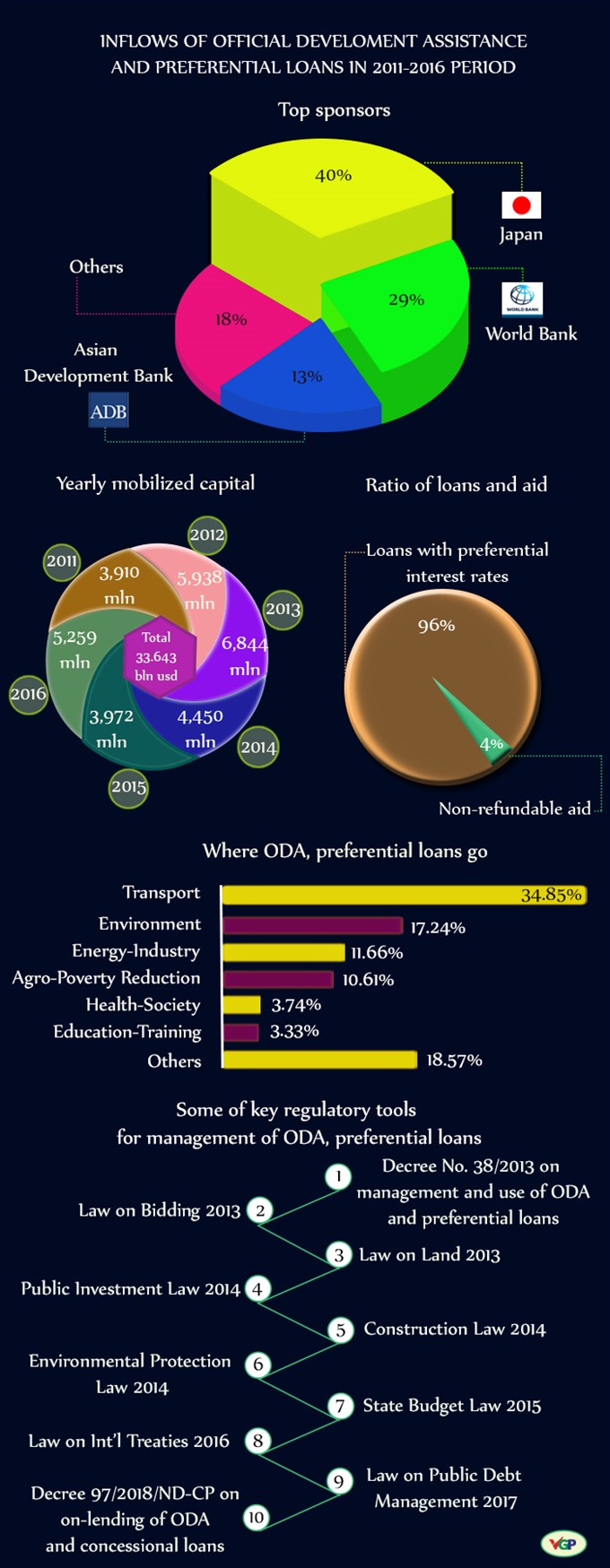

With such advantages over commercial lending, the volume of ODA that donors had committed to provide to Viet Nam used to be announced as a success after every Consultative Group Meeting (now called the Vietnam Development Partnership Forum).

Viet Nam was able to get out of the group of poor countries and join the low middle income nations in 2010 partly thanks to the aid of donor countries given in the form of ODA provision.

However, along with being lifted up to the middle income status, Viet Nam has been ineligible to enjoy concessional loans. Since July 2017, the World Bank, who used to provide 30 per cent of Viet Nam’s cheap loans to the country, has stopped offering ODA. The Asian Development Bank will also halt ODA to Viet Nam in January 2019.

Interest rates on existing ODA will gradually approach the market-based levels and the repayment period will be shortened by half.

In theory, the source of external capital has played a critical role in poor countries’ development stages. It is an important resource for promoting growth, reducing poverty, strengthening institution capacity and enhancing know-how management and technological transfer.

In fact, on the one hand, effectiveness of ODA is very much dependent on the motives of donors. Different donors have different motives to provide ODA, but they have a common ground that they must surely get certain benefits in return from their assistance. So, ODA is not a free lunch.

ODA is also not cheap as we think. Take into account other fees such as capital arrangement fee, then the real ODA transaction costs are probably higher than the interest rates of commercial loans in the domestic market.

According to the UNDP’s definition, ODA transaction costs are the cost arising from each stage of a project cycle, from preparation, negotiation, implementation, monitoring and enforcement of agreements for the delivery of ODA. The costs are usually high.

In addition, some donors even have requirements that recipients must use some selected technologies, contractors, and equipment suppliers, causing the actual borrowing cost to be higher than competitive bidding.

On the other hand, ODA has a positive impact on growth in developing countries with good policies but little effect in countries with poor policies.

The MPI points out that the capability of localities that host ODA projects was still limited. Some ongoing ODA projects had to extend their execution time due to delays in land clearance and slow construction progress.

For example, the investment capital for the ongoing project of Nhon-Ha Noi Station Urban Railway is now about 1.17 billion euros (US$1.3 billion) instead of 783 million euros as initially planned.

The report is a wake-up call for Viet Nam to review how it uses, manages and allocates the ODA capital.

Viet Nam and other donor countries and organisations have become development partners when the former is no longer the ODA recipient of the latter, but incentives do not stop abruptly.

Many partners have still pledged to provide preferential loans to Viet Nam, and to increase technical assistance to continue supporting the country’s economy. So we need not to refuse them all. Instead, we need to take advantages of them.

With the need to accelerate the economy at this stage, it is possible to see that cheap capital - including ODA - remains a good option for development.

Whether ODA will be the "trap" of the economy in the medium and long term depends on our ability to change ourselves. As recommended by the Minister of Planning and Investment, the Government should have a guide on attracting and using foreign loans for development in the period of 2021-25.

Accordingly, ODA capital should only be provided to programmes or projects designed with a sufficiently large scale to maximise effectiveness, have a strong spillover effect and meet development needs.

It is necessary to combine domestic borrowing and foreign borrowing, with the participation of private sector being strongly encouraged.

* Vo Tri Thanh is a senior economist at the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM) and a member of the National Financial and Monetary Policy Advisory Council. The holder of a doctorate in economics from the Australian National University, Thanh mainly undertakes research and provides consultation on issues related to macroeconomic policies, trade liberalisation and international economic integration. Other areas of interest include institutional reforms and financial systems.